What is Katsuobushi?

Katsuobushi, the most important ingredient in dashi at Japanese cuisine

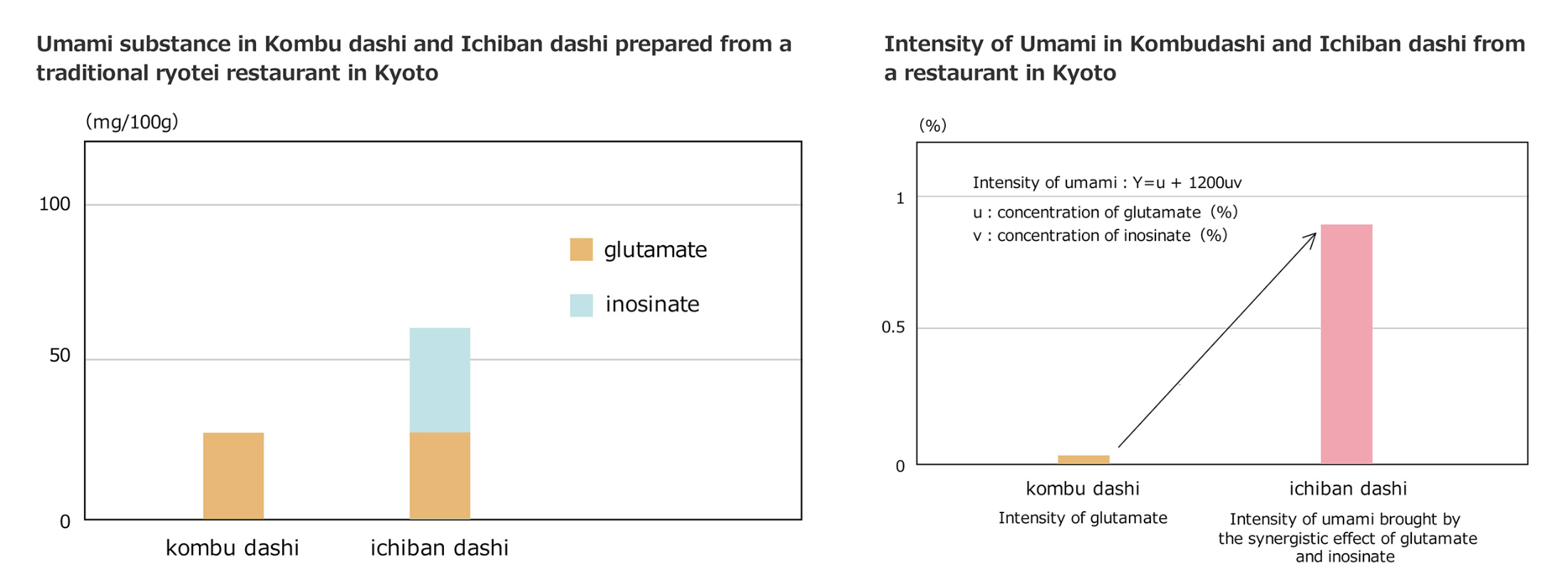

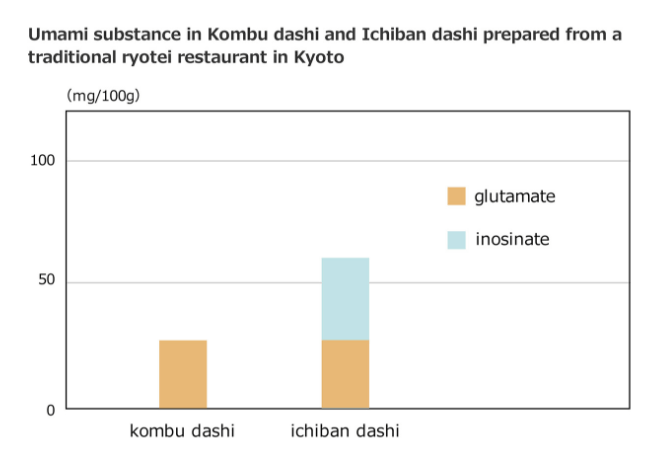

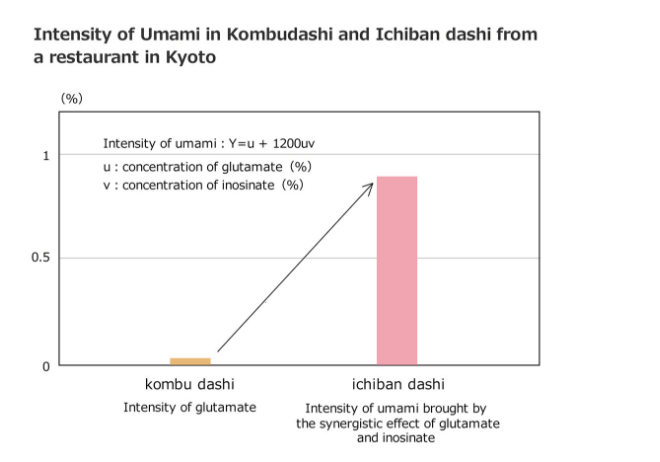

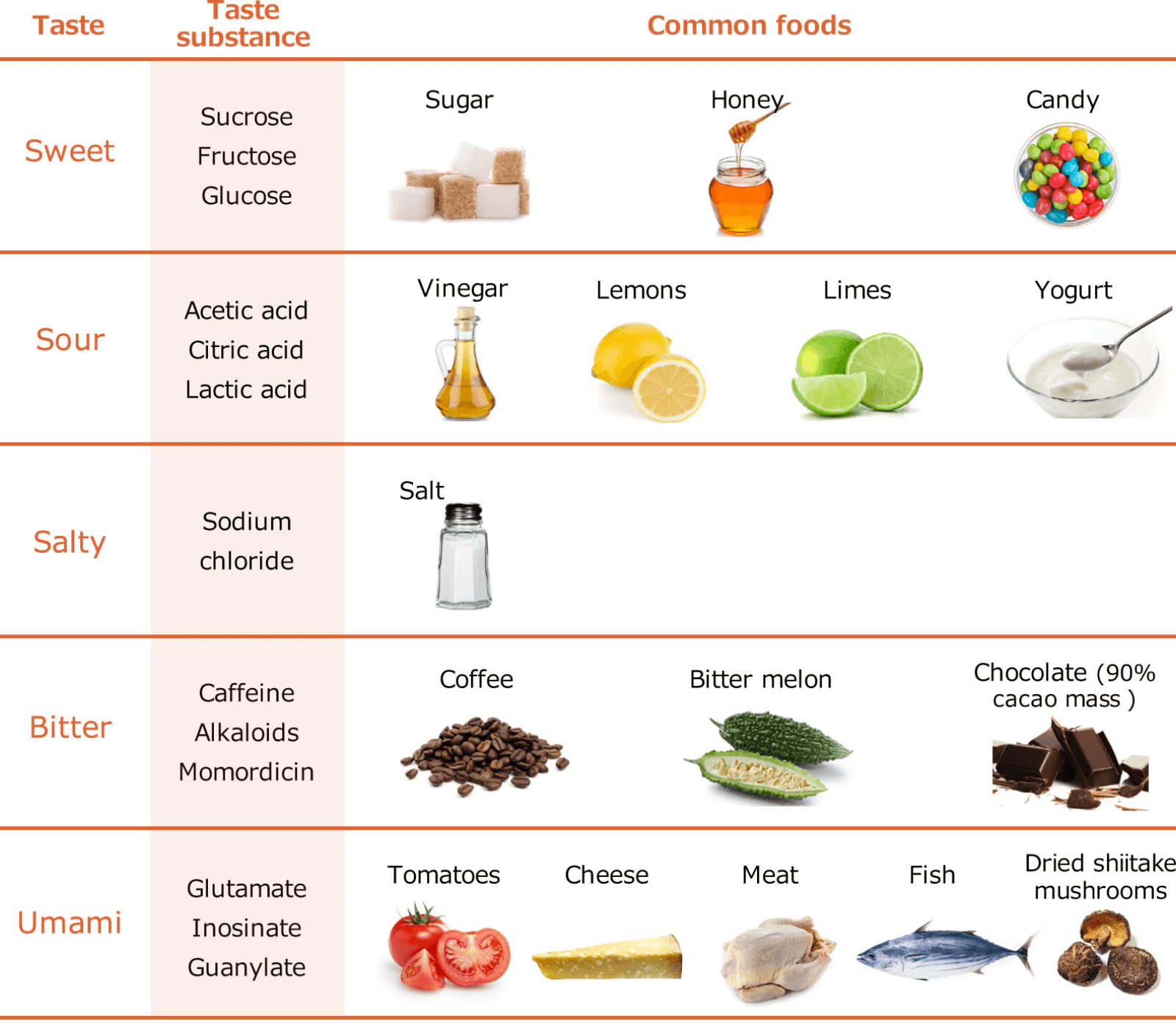

Katsuobushi is made of katsuo or bonito, skipjack tuna, a saltwater fish. Bonito is rich in protein. If unprocessed, it has a 25% protein content, and if used to make katsuobushi, its protein

content increases to 77%. It is also rich in inosinate, an important umami substance; the umami is multiplied many times over when combined with glutamate.

This is the mechanism behind ichiban dashi (“first soup stock”) in Japanese cuisine.

Katsuobushi is not just about smoking fish; the creation process is a tradition that has been handed down for over nearly 400 years. Making katsuobushi involves drying katsuo, introducing

beneficial mold that triggers fermentation, and creating a deeper, richer flavor. The process takes many months, and the end result is a surprisingly hard, richly flavorful food product. The finished katsuobushi is shaved

using a box grater.

The resulting flakes are used mainly for making dashi (stock). This method can use other kinds of fish, such as tuna, mackerel, and sardine.